In 2023, the Arkansas Legislature passed and Gov. Sarah Huckabee-Sanders signed into law Senate Bill 473, Freedom Foundation-supported legislation prohibiting public schools from using their taxpayer-funded payroll systems and personnel to collect union dues from teachers’ paychecks.

Although Natural State lawmakers prohibited collective bargaining between government employers and unions representing state and school district employees two years earlier, the 2021 legislation had inexplicably left intact an obligation that these government employers act as unions’ dues collectors.

A new Freedom Foundation analysis of tax returns filed by the Arkansas Education Association (AEA), the state teachers union and an affiliate of the Washington, D.C.-based National Education Association (NEA), shows a modest decline in AEA’s revenue from membership dues following the collective bargaining ban, but reveals a staggering 36 percent decline in union dues collection in the first full year following passage of SB 473.

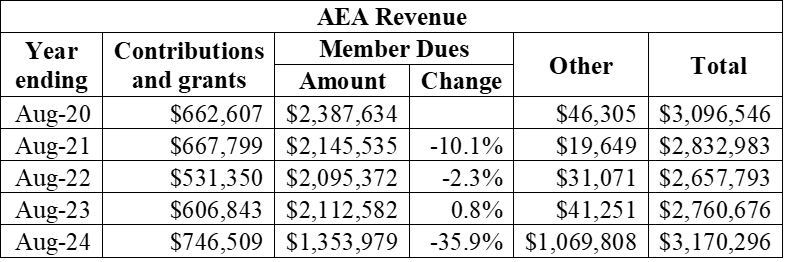

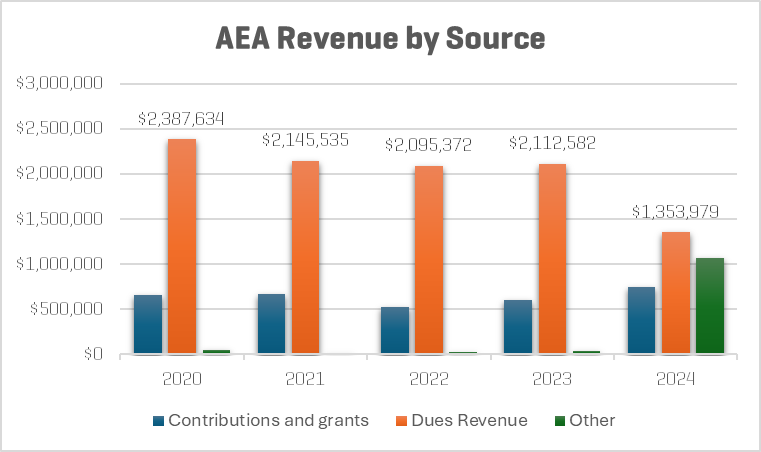

As a baseline, the AEA’s Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Form 990 tax return for the tax year ending August 31, 2020, reported nearly $2.4 million in revenue from membership dues.

Over the two years following the 2021 collective bargaining ban, AEA’s dues revenue declined by 10 percent in the year ending in August 2021 and by another 2 percent the year ending in August 2022, dropping to $2.1 million.

The union experienced a modest reprieve in fiscal year 2023, managing to bring in about 1 percent more dues revenue than it had the year prior.

But passage of SB 473 proved devastating, with the AEA’s dues revenue free-falling 36 percent in its first full year without the assistance of government union dues collection, dropping to less than $1.4 million in the tax year ending August 2024.

Unions like the AEA typically prefer to have government deduct union dues from employees’ paychecks, for several reasons. First, it saves the unions the time, expense, and administrative hassle of collecting dues themselves, placing the burden instead on taxpayer-funded government payroll systems and personnel. For instance, payroll deduction saves the unions from paying credit card processing fees on members’ dues payments.

Second, payroll deduction makes soliciting membership much easier. A union does not have to ask for employees’ credit card number or bank account information, nor does it have to even disclose the cost of union dues.

With payroll deduction, all a union needs to do is get an employee to sign on the dotted line to get direct access to their paycheck. Heavy-handed tactics — such as forging signatures on membership forms and locking people in a room until they sign — are not unheard of.

Coercive measures aside, the mere fact that the government is collecting the funds conveys a sense of legitimacy or even compulsion. Although no public employee can constitutionally be forced to pay union dues or fees, unions benefit from leaving employees with the impression that membership is at least expected, if not required.

Lastly, payroll deduction facilitates union policies restricting when employees can cancel their membership.

The NEA explains its ideal dues collection system as follows:

“Legislation should guarantee employee rights to payroll deduction of membership dues. Legislation should also require employers to implement payroll dues deductions in accordance with the terms of the authorization agreement between the union and their members. The terms of a member authorization may include a maintenance of payment provision in which employees agree to pay their full annual dues even if they choose to resign from union membership.”

That AEA revenue declined three times as much after the end of government dues collection than it did after the end of collective bargaining — the service most teachers generally think they are paying for when they join a union — shows just how coercive payroll deduction is.

If a union has to get people to pay for its services the same way any other business or organization does — by arranging payment directly via credit card, bank transfer, check or cash — its membership and revenue will be far lower than when the union is propped up by the government.

So far, Arkansas’ experience tracks with other states that have similarly ended government collection of union dues.

In Florida, for instance, the Florida Education Association lost 20,000 members in the first year following the passage of Freedom Foundation-supported legislation in 2023 ending payroll deduction of union dues. Other government unions in Florida saw their membership decline by more than a third.

While the AEA is not required to disclose its membership numbers, its loss of membership probably aligns closely with the decline in dues revenue. If anything, it is likely that the membership decline exceeded 36 percent, since unions typically collect more revenue from each individual member over time.

Interestingly, despite the precipitous drop in revenue from dues, AEA’s total revenue increased by over $400,000 due to additional grant funding from the NEA — essentially, NEA members from states like California are now subsidizing the AEA — as well as an infusion of $1.2 million from what the AEA’s tax return indicated was “from sales of assets other than inventory.”

If disclosed properly according to IRS directions, the revenue came not from the sale of “securities” like stocks or bonds, but from some other kind of “investment” like “real estate, royalty interests, or partnership interests” or “non-inventory assets.”

The most likely explanation would seem to be a real estate sale, but the AEA does not appear to have either sold its headquarters office just north of the state capitol in Little Rock or possess other real estate sufficient to generate such a sum.

In fact, the AEA’s 2023 Form 990 does not appear to disclose the existence of any assets that were liquidated during the union’s 2024 tax year. Instead, the sale appears to have come from out of thin air and appears on the union’s 2024 balance sheet as an infusion of cash.

Whatever the source, it is almost certainly a one-time lifeline. Absent some stark reversal in the AEA’s fortunes or additional, mysterious bailouts, the union will face some difficult decisions in the years ahead.