The Washington State Legislature adopted the education funding system improvements required by the Washington State Supreme Court, (HB 2242 of 2017 and SB 6362 of 2018).

The reality was that those funds were earmarked for a host of expenses, materials and services. The Legislature and the court acknowledged the importance of good compensation to provide for services to students. Providing attractive compensation was part of the goal, but the primary goal was to assure wages were state-funded, not local levy-funded.Predictably, the Washington Education Association (WEA) set out to capture a disproportionate share of those funds as wage increases, and its leaders sought to convince teachers that districts that didn’t provide “big pay raises” were stealing teachers’ money.Provision for education services has increased 68 percent while student enrollment grew by 9 percent.

The problem created by local salary enhancement was that the state needed to carry the responsibility to provide for the full cost of basic education, but local levy-funded wage enhancement allowed the state to shirk its duty.

Additionally, levy-funded wages allowed wage disparities between property-rich and property-poor districts to grow.

The legislative solution approved by the governor and the court did four things.

First, it increased the state property tax by about 80 to 90 cents per thousand dollars of assessed value.

Second, it increased the state-allocated per-teacher salary from $55,705 to $65,216 – a 17 percent hike.

Third, it ended districts’ ability to use levy funds to increase teachers’ wages above the state salary schedule. Most districts have previously agreed to contracts providing levy funds to enhance wages by 3 to 37 percent. The new state funding for teacher wages was supposed to backfill the reduction in levy-funded wages.

Fourth, it lowered the maximum property tax rate that could be set by local school levies since they were no longer to be used for wage funding.

The new state money was mostly intended to offset a reduction in local levy-funded salary enhancements. In districts which had not been able to use levies for wage enhancements, the increase would be large, but in most districts it would be modest as local levy funds cease to be available for wages. As a result, the state would be responsible for basic education and teacher wages would be more equitable across the state.

Unfortunately, this solution was intolerable for the union executives at WEA. They prefer to retain the ability to push for wage increases at both the state and local level. The union wasn’t willing to let districts comply with the laws ending this unsustainable and unfair practice.

WEA deceived teachers and the public about how state funding was supposed to be used, and it pushed districts to cannibalize levy-funded school services for families to feed the union’s wage increase demands.

WEA agitated for hard bargaining that ignored the laws capping negotiated raises at 3.1 percent and prohibiting levy money from being used for wage enhancements. The union instigated multiple strikes when some districts resisted.

Elected school boards were intimidated or were comprised of union-sympathizers, and they gave in to extraordinary wage demands. WEA posted a war map crowing about raises ranging from 12 percent to 34 percent.

These increases in school districts’ payroll obligations massively exceeded the salary funds provided by the state, which were set at $65,216 per teacher with some enhancements for districts with a high cost of living (Washington State Operating Budget, Section 503).

What happens when school districts promise more in salary than the state provides?

Despite years of unprecedented increases in state education funding, many districts are now facing significant budget shortfalls. This is because they have payroll obligations which will make their budgets unsustainable.

- “Vancouver Public Schools faces $11.4 million budget deficit,” The Columbian, Jan. 7, 2019

“Vancouver Public Schools projects an $11.4 million budget deficit in the coming school year, and it says salary deals with teachers and educational support staff are partly to blame.”

- “Vancouver Public Schools lists recommended budget cuts,” The Columbian, Jan. 22, 2019

“The cuts are being discussed to address an $11.44 million budget shortfall forecast for the school year, which district officials say is at least partially due to $7.2 million in costs from the contract agreement with the Vancouver Education Association after this past summer’s strike, and $2.1 million reflecting the district’s offer to the Vancouver Association of Educational Support Professionals.”

Union contract provides a 13.2 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Budget advisory group finalizes proposed cutbacks for Aberdeen School District,” The Daily World, Jan. 18, 2018

“the Budget Advisory Committee presented its proposed areas for cuts, which added up to about $650,000 of more than $3.5 million the district says it needs to save for the 2019-20 school year.”

Union contract provides a 19.5 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Seattle school district plans budget cuts, including some librarians to part time,” KNKX Radio, Jan. 22, 2019

“The Seattle school district has been warning for about a year that it faces a budget deficit in the 2019-20 school year. Now, the district has laid out its plans for making $39.7 million dollars’ worth of cuts, including removing assistant principals from some schools and reducing some librarians to part time.”

Union contract provides minimum 10.5 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Some Yakima school districts may have to begin cuts to make budget,” Yakima Herald, Dec. 3, 2018

“administrators need to decide on cuts to keep budgets sustainable during the coming years”

“Backlund said he anticipates some staff cuts going into next year”

- “Huge budget cuts, layoffs coming in some schools after McCleary decision,” KOMO News, Nov. 9, 2018

“Everett Public Schools announced plans to cut $6.5 million from its 2019-2020 budget, and an additional $11.5 million from the 2020-2021 budget.”

“Everett isn’t the only district facing deficits. The Tacoma School District is eliminating 19 administrative positions along with other spending cuts for a total savings of $16 million. The district says it still needs to shave $7.5 million before year’s end.”

- “Everett Public Schools says it faces budget cuts in latest fallout from McCleary-funded teacher pay hikes,” Seattle Times, Nov. 8, 2018

“The district expects to cut $6.5 million from next year’s budget, a number that will continue to rise for the following two years.”

- “Everett school district eyes layoffs as budget shortfall looms,” KING 5 News, Nov. 7, 2018

“Everett Public Schools is eyeing layoffs as it looks to cut $6.5 million from its 2019-20 budget. The district announced Wednesday it could also cut an additional $11.5 million in the 2020-21 school year and $5 million in the 2021-22 school year if the Legislature doesn’t provide an education funding fix.”

Union contract provides a 14 percent teacher pay raise.

- “In wake of teacher strike, Tacoma schools cutting several administrative positions,” KOMO News, Oct. 24, 2018

“The cuts aren’t over. The district says it still needs to shave $7.5 million from this year’s budget and more spending cuts will be needed in the next school year. ‘We would be looking throughout the district for spending cuts next school in addition to classroom positions,’ said Voelpel.”

- “Tacoma graduation rates are at a record high, but budget challenges pose threat,” The News Tribune, Jan. 11, 2019

“To offset the deficit, the district eliminated 40 positions this school year, totaling $23.8 million in savings. One of those positions was the assistant director of the English Language Learner program. . . . [T]he next step is tackling a significantly larger debt in the 2019-20 school year.

Union contract provides a 15.2 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Mount Vernon School District looking for input on cuts,” GoSkagit, Oct. 14, 2018.

“For the next school year, the district is looking to cut its budget by 4.5 to 5 percent — or between $4.5 million and $5 million, Superintendent Carl Bruner said.”

Union contract provides a 12 percent minimum teacher pay raise.

- “Spokane Public Schools planning to reduce staffing through attrition to pay for teacher raises,” The Spokesman Review, Sept. 20, 2018

“Redinger said the district is already moving to reduce a $12.6 million operating deficit.”

Union contract provides a 14.3 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Wenatchee schools faced with budgeting challenges,” The Wenatchee World, Sept. 18, 2018

“Last month, the Wenatchee School Board members approved a general fund budget of $114 million for the 2018-19 school year. It represents a roughly $11 million increase from the spending budget for the 2017-18 school year due to additional state funding made available through the McCleary Act. Still, the district will have to draw about $3 million from its shrinking reserve fund. ”

- “Wenatchee school budget survey ends Sunday,” Wenatchee World, Jan. 30, 2019

“Wenatchee parents, students, community members and school staff have until midnight Sunday to weigh in on how best to close a $5.2 million deficit in the Wenatchee School District’s budget.”

Union contract provides a 12 percent minimum teacher pay raise.

- “Big raises now may mean deficits later for public schools,” The Herald, Sept. 10, 2018.

- “Budget woes projected for Naselle-Grays River Valley schools,” Chinook Observer, Aug. 28, 2018

Union contract provides an 11.2 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Moses Lake school board OKs budget, warns of looming shortfalls,” Columbia Basin Herald, Aug. 26, 2016

“Board members unanimously approved this school year’s $124.2 million operating budget but was also seeking 5 percent — $6.2 million — in cuts to that budget as forecasts for the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years see the district’s operating shortfall as high as $25 million by 2021-22.”

Union contract provides an 11.9 percent teacher pay raise.

- “Longview school district faces budget deficits,” The Daily News, Aug. 16, 2018.

“In other words, over the next several years the district must increase revenues or cut expenses — or get the Legislature to change the McCleary legislation.”

- “Longview schools making cuts to pay for teacher, staff raises,” The Daily News, Dec. 22, 2018

“The Longview School District plans to delay adoption of new elementary science and social studies materials to make up for almost half of the $1 million budget overages created by recent pay raises for faculty and staff.”

- “Longview School Board considers budget guidelines for the district,” The Daily News, Jan. 14, 2019

“The district currently has about $9.9 million in budget reserves, but it expects that total to drop by more than 50 percent by the end of the next school year.”

Union contract provides a 9 percent teacher pay raise (in addition to the 10 percent raise provided last year)

- “Edmonds School District predicts $39M deficit by the end of 2022,” com, Aug. 12, 2018

Union contract provided 18.3 percent teacher pay raise.

Unfortunately, the kinds of things that can be cut to afford larger salaries include supplemental services for students falling behind, support staff, building maintenance, supplies, curriculum, professional training, and elective programs. Likewise, class sizes can increase by freezing hiring.

In other words, unsustainable salary increases reduce the services families receive from their schools despite large increases in funding.

It is important to fairly compensate teachers, but the influx of new state funds was sufficient for increases which did not break school district budgets and force cut backs in services.

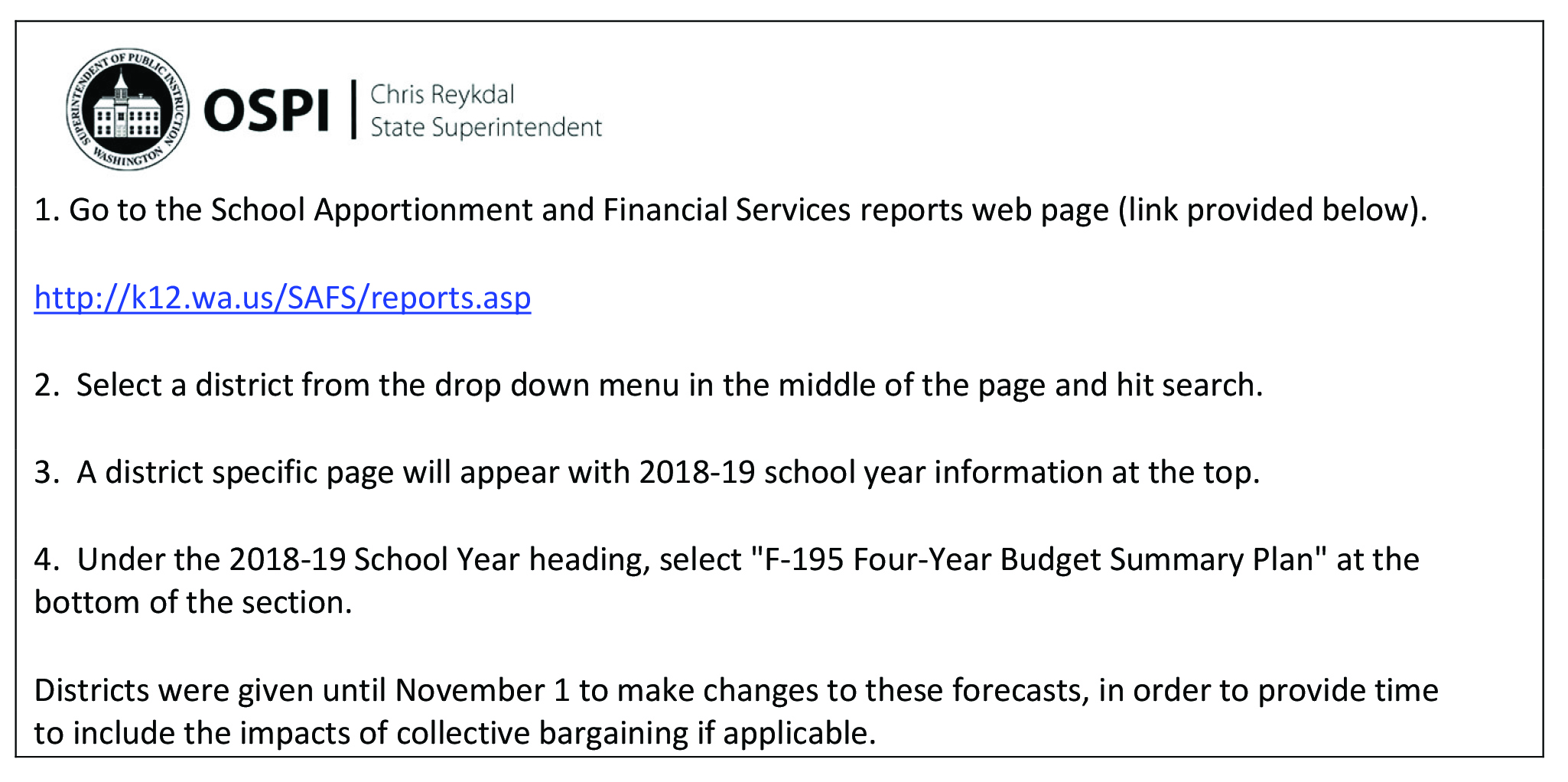

Look up your own district’s deficit on the state website

The state hoped that allowing districts to fully negotiate salary would result in sustainable budget proposals. To make sure, districts are now required to report their four-year budget plans to the state which makes them available on line. These are very likely optimistic, since districts guess their revenues when making these estimates.

On Nov. 8, the state made these available to the public, and most demonstrate an alarming rate of deficit spending. Check your school district to see how well your elected school board is doing.

- Go to the School Apportionment and Financial Services reports web page (link provided below).

http://k12.wa.us/SAFS/reports.asp

- Select a district from the drop down menu in the middle of the page and hit search.

- A district specific page will appear with 2018-19 school year information at the top.

- Under the 2018-19 School Year heading, select “F-195 Four-Year Budget Summary Plan” at the bottom of the section.

Districts were given until November 1 to make changes to these forecasts, in order to provide time to include the impacts of collective bargaining if applicable.

Related

What Can Be Learned From The Ferry System About Teacher Strikes?

If teacher strikes are illegal, why do they happen?

Tacoma teacher strike prompts legislators to hint at new property taxes

Has the legislature fixed public education?

Teachers In Mabton Are Marching For A 17 Percent Raise

Breaking community colleges for unions

Local offices to be filled this year

State superintendent favors union power

Senate nearly fixes education funding loophole

Open Letter to Lawmakers: Restore Sideboards on Collective Bargaining

Teachers union bargaining to steal materials from children

SPI Sues to End WEA’s Damage to Funding

Superintendent Dorn Acknowledges Union Abuse of Public Interest